TURKISH CUISINE

The Story of Turkish Food: Turkish Cuisine: Prologue

|

|

|

TURKISH CUISINE |

|

The Story of Turkish Food: Turkish Cuisine: Prologue |

For those who travel engaged in culinary pursuits, the Turkish Cuisine is a

very, curious one. The variety of dishes that make up the Cuisine, the ways they

all come together in feast-like meals, and the evident intricacy of each craft

offer enough material for life-long study and enjoyment. It is not easy to

discern a basic element or a single dominant feature, like the Italian

"pasta" or the French "sauce". Whether in a humble home, at

a famous restaurant, or at a dinner in a Bey's mansion, familiar patterns of

this rich and diverse Cuisine are always present. It is a rare art, which

satisfies your senses while reconfirming the higher order of society; community

and culture. A practical-minded child watching

Mother cook "cabbage dolma" on a lazy; gray winter day is bound to

wonder : "Who on earth discovered this peculiar combination of sautéed

rice, pine-nuts, currants, spices, herbs and all tightly wrapped in translucent

leaves of cabbage all exactly half an inch thick and stacked up on an oval

serving plate decorated with lemon wedges? How was it possible to transform this

humble vegetable to such heights of fashion and delicacy with so few additional

ingredients? And, how can such a yummy dish possibly also be good for one7" The modern mind, in a moment of

contemplation, has similar thoughts upon entering a modest sweets shop in Turkey

where "baklava" is the generic cousin of a dozen or so sophisticated

sweet pastries with names like : twisted turban, sultan, saray (palace), lady's

navel, nightingale's nest... The same experience awaits you at a "muhallebi"

(pudding shop) with a dozen different types of milk puddings.

Anyone who visits Turkey or has a meal

in a Turkish home, regardless of the success of the particular cook, is sure to

notice how unique the Cuisine is. Our intention here is to help the uninitiated

to enjoy Turkish food by achieving a higher level of understanding of the

repertoire of dishes, related cultural practices and their spiritual meaning.

Anatolia is a region known as the

"bread basket of the world." Turkey, is one of the seven countries in

the world which produces enough food to feed its own and then some to export.

The Turkish landscape encompasses such a wide variety of geographic zones, that

for every two to four hours of driving, you will find yourself in a different

zone with all the accompanying changes in scenery, temperature, altitude,

humidity, vegetation and weather conditions. The Turkish landscape has the

combined characteristics of the three old continents of the world : Europe,

Africa, and Asia, and an ecological diversity, surpassing any other place along

the 40th latitude. Thus, the diversity of the Cuisine has come to reflect that

of the landscape and its regional variations. In the Eastern Region, you will

encounter the rugged, snow-capped mountains where the winters are long and cold,

and the highlands where the spring season with its rich wild flowers and rushing

creeks extends into the long and cool summer. Livestock farming is prevalent.

Butter, yogurt, cheeses, honey meat and cereals are the local food. Long winters

are best endured with the help of yogurt soup and meat balls flavored with

aromatic herbs found in the mountains, and endless servings of tea. The heartland is dry steppe with

rolling hills, endless stretches of wheat fields and barren bedrock that takes

on the most incredible shades of gold, violet, and cool and warm grays as the

sun travels the sky Ancient cities were located on the trade routes with lush

cultivated orchards and gardens. Among these, Konya, the capital of the Selçuk

Empire (the first Turkish State in Anatolia), distinguished itself as the center

of a culture that attracted scholars, mystics, and poets from throughout the

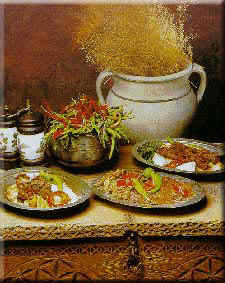

world during the l3th century The lavish Cuisine that is enjoyed in Konya today,

with its clay-oven (tandir) kebabs, böreks, meat and vegetable dishes and helva

desserts, dates back to the feasts given by Sultan Alaaddin Keykubad in 1237

A.D.

One

can only conclude that the evolution of this glorious Cuisine was not an

accident. Similar to other grand Cuisine of the world, it is a result of the

combination of three key elements. A nurturing environment is irreplaceable.

Turkey is known for an abundance and diversity of foodstuff due to its rich

flora, fauna and regional differentiation. And the legacy of an Imperial Kitchen

is inescapable. Hundreds of cooks specializing in different types of dishes, all

eager to please the royal palate, no doubt had their influence in perfecting the

Cuisine as we known it today The Palace Kitchen, supported by a complex social

organization, a vibrant urban life, specialization of labor, trade, and total

control of the Spice Road, reflected the culmination of wealth and the

flourishing of culture in the capital of a mighty Empire. And the influence of

the longevity of social organization should not be taken lightly either. The

Turkish State of Anatolia is a millenium old and so, naturally, is the Cuisine.

Time is of the essence; as Ibn'i Haldun wrote, "The religion of the King,

in time, becomes that of the People", which also holds for the King's food.

This, the reign of the Ottoman Dynasty during 600 years, and a seamless cultural

transition into the present day of modern Turkey led to the evolution of a grand

Cuisine through differentiation, refinement and perfection of dishes, as well as

their sequence and combination of the meals.

One

can only conclude that the evolution of this glorious Cuisine was not an

accident. Similar to other grand Cuisine of the world, it is a result of the

combination of three key elements. A nurturing environment is irreplaceable.

Turkey is known for an abundance and diversity of foodstuff due to its rich

flora, fauna and regional differentiation. And the legacy of an Imperial Kitchen

is inescapable. Hundreds of cooks specializing in different types of dishes, all

eager to please the royal palate, no doubt had their influence in perfecting the

Cuisine as we known it today The Palace Kitchen, supported by a complex social

organization, a vibrant urban life, specialization of labor, trade, and total

control of the Spice Road, reflected the culmination of wealth and the

flourishing of culture in the capital of a mighty Empire. And the influence of

the longevity of social organization should not be taken lightly either. The

Turkish State of Anatolia is a millenium old and so, naturally, is the Cuisine.

Time is of the essence; as Ibn'i Haldun wrote, "The religion of the King,

in time, becomes that of the People", which also holds for the King's food.

This, the reign of the Ottoman Dynasty during 600 years, and a seamless cultural

transition into the present day of modern Turkey led to the evolution of a grand

Cuisine through differentiation, refinement and perfection of dishes, as well as

their sequence and combination of the meals. It

is quite rare when all three of the above conditions are met, as they are in the

French, the Chinese and the Turkish Cuisine. The Turkish Cuisine has the extra

privilege of being at the cross-roads of the Far-East and the Mediterranean,

which mirrors a long and complex history of Turkish migration from the steppes

of Central Asia (where they mingled with the Chinese) to Europe (where they

exerted influence all the way to Vienna). All these unique characteristics and

history have bestowed upon the Turkish Cuisine a rich and varied n umber of

dishes, which can be prepared and combined with other dishes in meals of almost

infinite variety, but always in a non-arbitrary way This led to a Cuisine that

is open to improvisation through development of regional styles, while retaining

its deep structure, as all great works of art do. The Cuisine is also an

integral aspect of culture. It is a part of the rituals of everyday life events.

It reflects spirituality, in for ms that are specific to it, through symbolism

and practice.

It

is quite rare when all three of the above conditions are met, as they are in the

French, the Chinese and the Turkish Cuisine. The Turkish Cuisine has the extra

privilege of being at the cross-roads of the Far-East and the Mediterranean,

which mirrors a long and complex history of Turkish migration from the steppes

of Central Asia (where they mingled with the Chinese) to Europe (where they

exerted influence all the way to Vienna). All these unique characteristics and

history have bestowed upon the Turkish Cuisine a rich and varied n umber of

dishes, which can be prepared and combined with other dishes in meals of almost

infinite variety, but always in a non-arbitrary way This led to a Cuisine that

is open to improvisation through development of regional styles, while retaining

its deep structure, as all great works of art do. The Cuisine is also an

integral aspect of culture. It is a part of the rituals of everyday life events.

It reflects spirituality, in for ms that are specific to it, through symbolism

and practice.Nurturing Environment

Early

historical documents show that the basic structure of the Turkish Cuisine was

already established during the Nomadic Period, and in the first settled Turkish

States of Asia. Culinary attitudes towards meat, dairy products, vegetables and

grains that characterized this early period still make up the core of Turkish

Cuisine. Turks cultivated wheat and used it liberally in several types of

leavened and unleavened breads baked in clay ovens, on the griddle, or buried in

embers. "Mantı," ( dumpling), and "bugra," (attributed

to Bugra Khan of Turkestan, the ancestor of "börek" or dough with

fillings) were already among the much-coveted dishes at this time. Stuffing the

pasta, as well as all kinds of vegetables, was also common practice, and still

is, as evidenced by dozens of different types of "dolma". Skewering

meat as well as other ways of grilling, later known to us as varieties of

"kebab" and dairy products, such as cheeses and yogurt, were

convenient and staple foods of the pastoral Turks. They introduced these

attitudes and practices to Anatolia in the 11th century. In return they where

introduced to rice, the fruits, and the. vegetables native to the Region, and

the hundreds of varieties of fish in the three seas surrounding the Anatolian

Peninsula. These new and wonderful ingredients were assimilated into the basic

Cuisine in the millennia that followed.

Early

historical documents show that the basic structure of the Turkish Cuisine was

already established during the Nomadic Period, and in the first settled Turkish

States of Asia. Culinary attitudes towards meat, dairy products, vegetables and

grains that characterized this early period still make up the core of Turkish

Cuisine. Turks cultivated wheat and used it liberally in several types of

leavened and unleavened breads baked in clay ovens, on the griddle, or buried in

embers. "Mantı," ( dumpling), and "bugra," (attributed

to Bugra Khan of Turkestan, the ancestor of "börek" or dough with

fillings) were already among the much-coveted dishes at this time. Stuffing the

pasta, as well as all kinds of vegetables, was also common practice, and still

is, as evidenced by dozens of different types of "dolma". Skewering

meat as well as other ways of grilling, later known to us as varieties of

"kebab" and dairy products, such as cheeses and yogurt, were

convenient and staple foods of the pastoral Turks. They introduced these

attitudes and practices to Anatolia in the 11th century. In return they where

introduced to rice, the fruits, and the. vegetables native to the Region, and

the hundreds of varieties of fish in the three seas surrounding the Anatolian

Peninsula. These new and wonderful ingredients were assimilated into the basic

Cuisine in the millennia that followed.

Towards the west, one eventually reaches warm, fertile valleys between cultivated mountainsides, and the lace-like shores of the Aegean where nature is friendly and life has always been easy Fruits and vegetables of all kinds are abundant, including the best of all sea food! Here, olive oil becomes a staple and is used both in hot and cold dishes.

The temperate zone of the Black Sea Coast, well-protected by the high Caucasian Mountains, is abundant with hazelnuts, corn and tea. The Black Sea people are fishermen and identify themselves with their ecological companion, the shimmering "hamsi", a small fishes. Many poems, anecdotes and folk dances are inspired by this delicious fish.

The southeastern part of Turkey is hot and desert-like and offers the greatest variety of kebabs and sweet pastries. Dishes here are spicier compared to all other regions, possibly to retard spoilage in hot weather, or as the natives say to equalize the heat inside the body to that of the outside!

The culinary center of the country is the Marmara Region, which includes Thrace, with Istanbul as its Queen City This temperate, fertile region boasts a wide variety of fruits, vegetables, and the most delicately flavored lamb. The variety of fish that travel the Bosphorus surpasses those in other seas. Bolu, a city on the mountains, supplied the greatest cooks for the Sultan's Palace, and even now the best chefs in the country come from Bolu. Istanbul, of course, has been the epicenter of the Cuisine, and an understanding of Turkish Cuisine will never be complete without a survey of the Sultan's kitchen...

The importance of culinary art for the Ottoman Sultans is evident to every visitor of Topkapı Palace. The huge kitchens were housed in several buildings under ten domes. By the l7th century some thirteen hundred kitchen staff were housed in the Palace. Hundreds of cooks, specializing in different categories of dishes such as soups, pilafs, kebabs, vegetables, fish, breads, pastries, candy and helva, syrup and jams and beverages, fed as many as ten thousand people a day and, in addition, sent trays of food to others in the city as a royal favor.

The

importance of food has been also evident in the structure of the Ottoman

military elite, the Janissaries. The commanders of the main divisions were known

as the Soupmen, other high ranking officers were the Chief Cook, Scullion,

Baker, and Pancake Maker, though their function had little to do with these

titles. The huge cauldron used to make pilaf had a special symbolic significance

for the Janissaries, as the central focus of each division. The kitchen was also

the center of politics, for whenever the Janissaries demanded a change in the

Sultan's Cabinet, or the head of a grand vizier, they would overturn their pilaf

cauldron. "Overturning the cauldron," is an expression still used

today to indicate a rebellion in the ranks.

The

importance of food has been also evident in the structure of the Ottoman

military elite, the Janissaries. The commanders of the main divisions were known

as the Soupmen, other high ranking officers were the Chief Cook, Scullion,

Baker, and Pancake Maker, though their function had little to do with these

titles. The huge cauldron used to make pilaf had a special symbolic significance

for the Janissaries, as the central focus of each division. The kitchen was also

the center of politics, for whenever the Janissaries demanded a change in the

Sultan's Cabinet, or the head of a grand vizier, they would overturn their pilaf

cauldron. "Overturning the cauldron," is an expression still used

today to indicate a rebellion in the ranks.

It was in this environment that hundreds of the Sultans' chefs, who dedicated their lives to their profession, developed and perfected the dishes of the Turkish Cuisine, which was then adopted by the kitchens of the provinces ranging from the Balkans to Southern Russia, and reaching North Africa. Istanbul was the capital of the world and had all the prestige, so that its ways were imitated. At the same time, it was supported by an enormous organization and infrastructure, which enabled all the treasures of the world to flow into it. The provinces of the vast Empire were integrated by a system of trade routes with refreshing caravanserais for the weary merchants and security forces. The Spice Road, the most important factor in culinary history was under the full control of the Sultan. Only the best ingredients were allowed to be traded under the strict standards established by the courts.

Guilds played an important role in development and sustenance of the Cuisine. These included hunters, fishermen, cooks, kebab cooks, bakers, butchers, cheese makers and yogurt merchants, pastry chefs, pickle makers, and sausage merchants. All of the principal trades were believed to be sacred and each guild traced its patronage to the Prophets and Saints. The guilds prevailed in pricing and quality control. They displayed their products and talents in spectacular floats driven through Istanbul streets during special occasions, such as the circumcision festivities for the Crown Prince or religious holidays.

Following the example of the Palace, all of the grand Ottoman houses boasted elaborate kitchens and competed in preparing feasts for each other as well as the general public. In fact, in each neighborhood, at least one household wouldopen its doors to anyone who happened to stop by for dinner during the holy month of Ramadan, or during other festive occasions. This is how the traditional Cuisine evolved and spread, even to the most modest corners of the country

A survey of types of dishes according to their ingredients, may be helpful to explain the basic structure of the Turkish Cuisine. Otherwise it may appear to have an overwhelming variety of dishes, each with a unique combination of ingredients, way of preparation and presentation. All dishes can be conveniently categorized into: grain-based, grilled meats, vegetables, fish and sea food, desserts and beverages.

Before

describing each of these categories, some general comments are necessary The

foundation of the Cuisine is based on grains (rice and wheat) and vegetables.

Each category of dishes contains only one or two types of main ingredients.

Turks are purists in their culinary taste; the dishes are supposed to bring out

the flavour of the main ingredient rather than hiding it behind sauces or

spices. Thus, the eggplant should taste like eggplant, lamb like lamb, pumpkin

like pumpkin. Contrary to the prevalent Western impression of Turkish food,

spices and herbs are used very sparingly and singularly. For example, either

mint or dill weed are used with zucchini, parsley with eggplant, a few cloves of

garlic has its place in some cold vegetable dishes, cumin is sprinkled over red

lentil soup or mixed in ground meat when making "kġfte." Lemon and

yogurt are used to complement both meat and vegetable dishes, to balance the

taste of olive oil or meat. Most desserts and fruit dishes do not call for any

spices. So their flavors are refined and subtle.

Before

describing each of these categories, some general comments are necessary The

foundation of the Cuisine is based on grains (rice and wheat) and vegetables.

Each category of dishes contains only one or two types of main ingredients.

Turks are purists in their culinary taste; the dishes are supposed to bring out

the flavour of the main ingredient rather than hiding it behind sauces or

spices. Thus, the eggplant should taste like eggplant, lamb like lamb, pumpkin

like pumpkin. Contrary to the prevalent Western impression of Turkish food,

spices and herbs are used very sparingly and singularly. For example, either

mint or dill weed are used with zucchini, parsley with eggplant, a few cloves of

garlic has its place in some cold vegetable dishes, cumin is sprinkled over red

lentil soup or mixed in ground meat when making "kġfte." Lemon and

yogurt are used to complement both meat and vegetable dishes, to balance the

taste of olive oil or meat. Most desserts and fruit dishes do not call for any

spices. So their flavors are refined and subtle.

There are major classes of meatless dishes. When meat is used, it is used sparingly Even with the meat kebabs, the "pide" or the flat bread occupies the largest part of the portion along with vegetables or yogurt. The Turkish Cuisine also boasts a variety of authentic contributions in the desserts and beverage categories. For the Turks, the setting is as important as the food itself. Therefore, food-related places need to be surveyed, as well as the dishes and the eating-protocol. Among the "great good places" where you can find the ingredients for the Cuisine, are the weekly neighborhood markets "pazar", and the permanent markets. The most famous one of the latter type is the Spice Market in Istanbul. This is a place where every conceivable type of food item can be found, as it has always been since pre-Ottoman times. This is a truly exotic place, with hundreds of scents rising from stalls located within an ancient domed building, which was the terminal for the Spice Road. More modest markets can be found in every city center, with permanent stalls of fish and vegetables.

The weekly markets are where sleepy neighborhoods come to life, with the villagers setting up their stalls before dawn at a designated area, to sell their products. On these days, handicrafts, textiles, glassware and other household items are also among the displays at the most affordable prices. What makes these places unique is the cacophony of sights, smells, sounds and activity, as well as the high quality of fresh food, which can only be obtained in the pazar. There is a lot of haggling and jostling, as people make their way through the narrow isles while the vendors compete for attention. One way to purify body and soul would be to rent an inexpensive flat by the seaside for a month every year, and live on fresh fruit and vegetables from the pazar. However, since the more likely scenario will be restaurant-hopping, here are some tips to learn the proper terminology so that you can navigate through both, the Cuisine (just in case you get the urge to cook a la Turca), and the streets of Turkish cities, where it is just as important to locate the eating places as the museums and the archaeological wonders.

Eating

is taken very seriously in Turkey It is inconceivable for the household members

to eat alone, raid the refrigerator, or eat on the "go", while others

are at home. It is custom to have three "sit-down meals" a day.

Breakfast or "kahvaltı" (literally 'foundation for

coffee),

typically consists of bread, feta cheese, black olives and tea. Many work places

have lunch served as a contractual fringe benefit. Dinner starts when all the

family members get together and share the events of the day at the table. The

menu consists of three or more types of dishes that are eaten sequentially

accompanied by salad. In summer, dinner is served at about eight. Close

relatives, best friends or neighbors may join meals on a "walk-in"

basis. Others are invited ahead of time as elaborate preparations are expected.

The menu depends on whether alcoholic drinks will be served or not. In the

latter case, the guests will find the meze spread ready on the table, frequently

set up either in the garden or on the balcony. The main course is served several

hours later. Otherwise, the dinner starts with soup, followed by the meat and

vegetable main course, accompanied by the salad. Then the olive-oil dishes such

as the dolmas are served, followed by dessert and fruit. While the table is

cleared, the guests retire to the living room to have a tea and

Turkish coffee.

Eating

is taken very seriously in Turkey It is inconceivable for the household members

to eat alone, raid the refrigerator, or eat on the "go", while others

are at home. It is custom to have three "sit-down meals" a day.

Breakfast or "kahvaltı" (literally 'foundation for

coffee),

typically consists of bread, feta cheese, black olives and tea. Many work places

have lunch served as a contractual fringe benefit. Dinner starts when all the

family members get together and share the events of the day at the table. The

menu consists of three or more types of dishes that are eaten sequentially

accompanied by salad. In summer, dinner is served at about eight. Close

relatives, best friends or neighbors may join meals on a "walk-in"

basis. Others are invited ahead of time as elaborate preparations are expected.

The menu depends on whether alcoholic drinks will be served or not. In the

latter case, the guests will find the meze spread ready on the table, frequently

set up either in the garden or on the balcony. The main course is served several

hours later. Otherwise, the dinner starts with soup, followed by the meat and

vegetable main course, accompanied by the salad. Then the olive-oil dishes such

as the dolmas are served, followed by dessert and fruit. While the table is

cleared, the guests retire to the living room to have a tea and

Turkish coffee.

Women get together for afternoon tea at regular intervals (referred to as the "7-17 days") with their school-friends and neighbors. These are very elaborate occasions with at least a dozen types of cakes, pastries, finger foods and böreks prepared by the hostess. The main social purpose of these gatherings is to share information and experience about all aspects of life, public and private. Naturally, one very important function is the propagation of recipes. Diligent exchanges occur while women consult each other on their innovations and solutions to culinary challenges.

By

now it should be clear that the concept of having a "pot-luck" at

someone's house is entirely foreign to the Turks. The responsibility of

supplying all the food squarely belongs to the host who expects to be treated in

the same way in return. There are two occasions where the notion of

"host" does not apply One such situation is when neighbors collaborate

in making large quantities of food for the winter such as "tarhana" -

dried yogurt/tomato soup, or noodles. Another is when families get together to

go on a day's excursion into the countryside. Arrangements are made ahead of

time as to who will make the köfte, dolma, salads, pilafs and who will supply

the meat, the beverages and the fruits. The "mangal" - the copper

charcoal burner, kilims, hammocks, pillows, musical instruments such as saz, ud,

or violin, and samovars are loaded up for a day trip.

By

now it should be clear that the concept of having a "pot-luck" at

someone's house is entirely foreign to the Turks. The responsibility of

supplying all the food squarely belongs to the host who expects to be treated in

the same way in return. There are two occasions where the notion of

"host" does not apply One such situation is when neighbors collaborate

in making large quantities of food for the winter such as "tarhana" -

dried yogurt/tomato soup, or noodles. Another is when families get together to

go on a day's excursion into the countryside. Arrangements are made ahead of

time as to who will make the köfte, dolma, salads, pilafs and who will supply

the meat, the beverages and the fruits. The "mangal" - the copper

charcoal burner, kilims, hammocks, pillows, musical instruments such as saz, ud,

or violin, and samovars are loaded up for a day trip.

A 'picnic' would be a pale comparison to these occasions, often referred to as "stealing a day from fate." Küçüksu, Kalamış, and Heybeli in old Istanbul used to be typical locations for such outings, as many songs tell us. Other memorable locations include the Meram vineyards in Konya, Hazer Lake in Elazığ, and Bozcaada off the shores of Çanakkale. Commemorating two Saints: Hızır and Ilyas (representing immortality and abundance), the May 5th Spring Festival Hıdırellez) would mark the beginning of the pleasure-season (safa), with romantic affairs, lots of poetry songs and, naturally, good food.

A similar "safa" used to be the weekly trip to the Turkish Bath. Food prepared the day before, would be packed on horse-drawn carriages along with fresh clothing and scented soaps. After spending the morning at the marble wash-basins and the steam hall, people would retire to the wooden settees to rest, eat and dry off before returning home.

These days, such leisurely affairs are all but gone, spoiled by modern life. Yet, families still attempt to steal at least one day from fate every year, even though fate often triumphs. Packing food for trips is so traditional that even now it is common for mothers to pack some köfte, dolma and börek to go on an airplane, especially on long trips, much to the bemusement of other passengers and the irritation of flight attendants. But seriously given the quality of airline food, who can blame them?

Weddings, circumcision ceremonies, and holidays are celebrated with feasts. At a wedding feast in Konya, a seven course meal is served to the guests. The "sit-down meal" starts with a soup, followed by pilaf and roast meat, meat dolma, and saffron rice - a traditional wedding dessert. Börek is served before the second dessert, which is typically the semolina helva. The meal ends with okra cooked with tomatoes, onions, and butter with lots of lemon juice. This wedding feast is typical of Anatolia, with slight regional variations. The morning after the wedding the groom's family sends trays of baklava to the bride's family

During the holidays, people are expected to pay short visits to each and every friend within the city visits which are immediately reciprocated. Three or four days are spent going from house to house, so enough food needs to be prepared and put aside to last the duration of the visits. During the holidays, kitchens and pantries burst at the seams with bġreks, rice dolmas, puddings and desserts that can be put on the table without much preparation. Deaths are also occasions for cooking and sharing food. In this case, neighbors prepare and send dishes to the bereaved household for three days after the death. The only dish prepared by the household of the deceased is the helva which is sent to the neighbors, who will remember and pray for the departed. In some areas, it is a custom for a good friend of the deceased to begin preparing the helva, while recounting fond memories and events. Then the spoon would be passed to the next person who would take up stirring of the helva and continue reminiscing. Usually the helva will be done by the time everyone in the room has had a chance to speak and stir the helva. This wonderful simple ceremony by making people left behind talk about happier times, lightens up their grief momentarily and strengthens the bond between them.

Food and dietary practices have always played an important part in all religions. Among them, Islam is perhaps known to impose the most elaborate and strict rules in this respect. In practice, these rules have been reinterpreted in regional adaptations, particularly in Turkey where it is harder to find strict Muslims. In Anatolia, where a variety of Sufi orders flourished, food gained a spiritual dimension above dry religious requirements, as can be seen in their poetry music, and practices.

Paradoxically,

the month of Ramadan, when all Muslims are expected to fast from dawn to dusk,

is also a month of feasting and charitable feeding of all those who are in need.

Fasting is to purify the body and the soul and at the same time, to develop a

reverence for all blessings bestowed by nature and cooked by a skillful chef.

The days are spent preparing food for the breaking of the fast at sunset. It is

customary to break the fast by eating a bite of "heavenly" food such

as olives or dates and nibbling lightly on a variety of cheeses, slices of

sausage, jams and pide. This would be followed by the evening prayers and then

the main meal. In the old days, the rest of the night would be occupied by games

and conversations, or going into town to attend the various musicals and

theaters, until it was time to eat again just before firing of the cannon or

beating of the drums marking the beginning of the next day's fasting. People

would rest until noon, when shops and work places opened and food preparation

began...

Paradoxically,

the month of Ramadan, when all Muslims are expected to fast from dawn to dusk,

is also a month of feasting and charitable feeding of all those who are in need.

Fasting is to purify the body and the soul and at the same time, to develop a

reverence for all blessings bestowed by nature and cooked by a skillful chef.

The days are spent preparing food for the breaking of the fast at sunset. It is

customary to break the fast by eating a bite of "heavenly" food such

as olives or dates and nibbling lightly on a variety of cheeses, slices of

sausage, jams and pide. This would be followed by the evening prayers and then

the main meal. In the old days, the rest of the night would be occupied by games

and conversations, or going into town to attend the various musicals and

theaters, until it was time to eat again just before firing of the cannon or

beating of the drums marking the beginning of the next day's fasting. People

would rest until noon, when shops and work places opened and food preparation

began...

The other major religious holiday is the "Sacrifice Holiday," commemorating Abraham's readiness to sacrifice his son Ishmael in the name of God. But God sent him a ram instead, sparing his son's life. The act of sacrificing an animal, in Turkey most likely a sheep, represents repentance and a solemn promise to do good on earth. The meat is sent to neighbors and to the needy. The sheep is revered as the creature of God that gives its life for a higher purpose. The henna colouring on the sheep is a symbolic way of showing this respect and so are the strict instructions for slaughtering. In fact, it is believed that one of these rams will take the believer across the "hair-thin and razor-sharp bridge" to heaven on Judgement Day.

Several other occasions commemorating Prophets also involve food. The six holy nights marking events in Prophet Mohammed's life are celebrated by baking special pastries, breads and lokma. The month of "Muharrem" occurred when the flood waters receded, and Noah and his family were able to land. It is believed that then they cooked a meal using whatever remained in their supplies. This event is celebrated by cooking the same dish -"aşure" or Noah's pudding, made of wheat berries, dried legumes, rice, raisins, currants, dried figs, dates and nuts. You can also taste this most nourishing pudding at certain muhallebi shops any time.

The feast of the Prophet Zaccharia is prepared upon being granted one's wish. This feast consists of a spread of forty-one different types of dried fruits and nuts served to guests. Prayers are read and everyone tastes all forty-one foods. A guest can then burn a candle and make a wish. If the wish comes true, one is obligated to prepare a similar "Zaccharia Table" for others.

Beyond these practices, examples of a spiritual tradition imbued with food metaphors are found in Sufism generally and in the poetry of Mevlana Celaleddin Rumi in particular, as well in the verses of classical Turkish poetry and music. In fact, to understand the full meaning of this spiritual tradition would be impossible without deciphering the references to food and wine, cooking, eating, and intoxication. Mevlana, who lived in Konya in the l3th century A.D., represents an approach to Sufism that follows the Way of Love to Divine Reality, rather than Knowledge, or gnosis. As mentioned earlier, the food-related guilds and the Janissaries also followed the Sufi Order. A clash of philosophies on food is told in a story about Empress Eugenie's French chef, who was sent to the Sultan's kitchen to learn how to cook an eggplant dish. He soon begged to be excused from this impossible task, saying that when he took his book and scales with him, the Turkish chef threw all of them out the window because "an Imperial chef must learn to cook with his feelings, his eyes and his nose" - in other words, with love!

Asceticism, rather than hedonistic gluttony is associated with Sufism, and yet food occupies an important place. Followers of the Order began with the simplest menial duties in dervish lodges which always included huge kitchens. After a thousand and one days of service, the novice would become "cooked" and become a full member of the Brotherhood. In other woods, being "cooked" refers to spiritual maturation. One wonders if the Turkish tradition of cooking everything until soft and well-done had anything to do with this association (cooking al dente has no meaning to Turks).

The story of the chick-pea told by Mevlana in his "Mathnawi" is a superb example of this idea. When the tough legume is cooked in boiling water, it complains to the woman cooking it. She explains to it that this is necessary so that it can be eaten by human beings, become part of human life and thus be elevated to a higher form of life. The fable of the chick-pea describes the suffering of the soul before its arrival at Divine Love. The peasant eating helva for the first time symbolizes the discovery of Divine Love by the dervish. There is also the image of God Himself preparing the helva for the true dervishes. In this particular verse, the whole universe, as it were, is pictured as a huge pan with the stars as cooks! In other verses, the Beloved (God) is described as being as tasty as salt, or the Friend (God) has "sugar lips." Wine also represents the maturation of the human soul, similar to the ordeal the sour grape endures. So many mystical meanings are attributed to wine that the name "tavern" stands for the Sufi hospice and experiencing Divine Love is described by the metaphor of "intoxication".

These spiritual ideas are still very much alive in present-day Turkey, where food and liquor are enjoyed with recitations of mystical poetry and dignified conversation. Often these gatherings provide an occasion for people to distance themselves from earthly matters and transcend into spirituality and promises of a better life hereafter.

As modernity takes hold, traditions are falling to one side. Spirituality as a guide for conduct in everyday life is something of the past; now we turn to Science for answers. Ironically as Mac Donald's and Pizza Huts are popping up everywhere, the traditional way of eating is also making a come-back. What our grandmothers knew all the time is now being confirmed by modern science : a diet which is fundamentally based on grains, vegetables and fruits with meat and dairy products used sparingly and as flavoring, is a healthy one. Furthermore, some combinations are better than others, because they complement each other for perfect nutrition. The Turkish Cuisine sets an example in these respects. The recent "food-pyramid" endorsed by the United States Department of Agriculture resembles age-old practices in ordinary households. Even the well-known menus of boarding schools or army kitchens, hardly known for their gourmet characteristics, provide excellent nutrition that can be JUSTIFY with the best of today's scientific knowledge. One such combination, jokingly referred to as "our national food," is beans and pilaf, accompanied by pickles and quince compote - a perfectly nourishing combination which provides the essential proteins, carbohydrates and minerals. Another curious practice is combining spinach with yogurt. Now we know that the body needs calcium found in the yogurt to assimilate the iron found in the spinach.

Yogurt, a contribution from the Turks to the world, has also become a popular health food. A staple in the Turkish diet, it has been known all along for its detoxifying properties. Other such beliefs, not yet supported by modern science, include the role of onion, used liberally in all dishes in strengthening the immune system; garlic for high blood pressure and olive oil as a remedy for forty-one ailments. The complicated debace concerning mono-and polyunsaturated fats and the good and bad cholesterol is ridiculously inadequate to evaluate olive oil. Given what we know about health food today one could even envy the typical lunch fare of the proverbial construction worker who, like all his kind, shouts "endearing" words to the passing-by females, while eating bread, feta cheese and fresh grapes in the summer and bread and tahini helva in the winter.

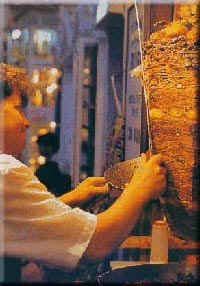

The

variety of pastry turn-overs with cheese or ground meat, meat pide, or kebabs

are the fast food for millions of working people. These are all prepared

entirely on the premises using age-old practices.

The

variety of pastry turn-overs with cheese or ground meat, meat pide, or kebabs

are the fast food for millions of working people. These are all prepared

entirely on the premises using age-old practices.

One of the main culprits in the modern-day diet is the snack, that horrible junk food designed to give a quick sugar-high to keep one going for the rest of the day. Again, modern science has come to the rescue, and healthy snacks are now being discovered. Some of these are amazingly familiar to the Turks! Take, for example, the "fruit roll-ups." Visit any dried-food store that sells nuts and fruits, and you will see the authentic version, such as the sheets of mashed and dried apricots and grapes. In these stores, there are many other items that await discovery by some pioneering entrepreneur to the Western markets. Another wholesome snack, known as "trail mix" or "gorp," is well-known to all Turkish mothers, who traditionally stuff a handful of mixed nuts and raisins in the pockets of their children's school uniform to snack on before exams. This practice can be traced to ancient fables, where the hero goes on a diet of hazelnuts and raisins before fighting with the giants and dragons, or before weaving the king a golden smock. The Prince always loads onto the mythological bird, the "Zümrüt Anka," forty sacks of nuts and raisins for himself, and water and meat for the bird that takes him over the high Caucasus Mountains...

As far as food goes, it is reassuring to know that we are re-discovering what is good for our bodies. Nevertheless, one is left with the nagging feeling that such knowledge will always be incomplete as long as it is divorced from its cultural context and spiritual traditions. The challenge facing modern Turkey is to achieve such continuity in a time of genetic engineering, high-tech mass production and a growing number of convenience-oriented households. But for now the markets are vibrant and the dishes are tastier than ever, so enjoy!

More Information About Turkish Coffee..!

Go Back to All About Turkey / Türkiye Hakkındaki Herşeye Dön

![]()

Home | Ana

Sayfa | All About Turkey | Turkiye

hakkindaki Hersey | Turkish Road Map

| Historical Places in Adiyaman | Historical

Places in Turkey | Mt.Nemrut | Slide

Shows | Related Links | Guest

Book | Disclaimer | Send a Postcard | Travelers' Stories | Donate a little to help | Getting Around Istanbul | Adiyaman Forum

|

|