[Cultural heritage of mankind] [Kommagene Kingdom] [Dances and Costumes]

|

|

|

[Cultural heritage of mankind] [Kommagene Kingdom] [Dances and Costumes] |

Adiyaman

region is

one of the earliest settled areas of the world. Archeological

evidence suggests that Adiyaman's history stretches back some 40,000

years. In fact cave paintings (those at Palanlı Mountain), and stone tools

(those found in Gıre Moza) in the region indicate a history that is around

100,000 old. At the end of the last ice age, about 10 to 15 thousand years ago,

the receding ice left behind very fertile land. Agriculture slowly replaced

hunting gathering as a way of life, resulting permanent settlements around the

region. According to archeological records, domestication of animals and

cultivating grains like barley and wheat started about 8-9 thousand years ago.

About this time too, one-room cone shaped houses, still present in Harran Valley

started to appear.

Other

Names Used for Adiyaman: Adiyaman is the name used for the province

since the establishment of the Turkish Republic. The name is a derivative of the

phrase, Vadi-i Leman (Pretty Valley) which over time through permutations of

pronunciation resulting in Adiyaman.

The ancient name of the region was Perre (Pirin). During the Islamic period it was called Hısnı Mansur, Semsur for short. During the Roman period the city was also called Klolzya in honor of the emperor Klozyos.

Shortly after the disintegration of Alexanders Empire,

Kommagene emerged in the west of the Euphrates River as a buffer kingdom between

the Persian and Roman Empires. The kingdom included current day provinces of Adiyaman,

Gaziantep, Maraş, and Kilis and existed between 162 BCE and 72 ACE. The

kingdom, whose capital was the city of Samasota, lived its golden age between 69

BCE and 36 ACE starting with the rein of King Antiochus I. Antiochus claimed

blood ties to the Persian emperors from his fathers side and to Roman the

emperors from his mothers. The name Kommagene comes from the local dialect,

which means everybodys kingdom.

Antiochuss biggest achievement was the construction of

a temple and tumulus on Mt. Nemrut 7,500 feet above sea level, considered the 8th

wonder of the world. From this site other significant monuments, including those

at Arsemia (kingdoms summer capital), burial sites at Fırlaz village and

Karakuş, and the tumulus at Karadağ.

The discovery of Mt. Nemrut was by accident. In 18383

Helmut Von Moltke, who was assigned to the Taurus army of the Ottoman Empire

came upon the statues during a field trip. He reported this the Prussian king;

the rest is history. Systematic archeological study of the mountain started in

1938 with the digs conducted by Otto Puchstein and Karl Sester. But the mountain

owes its worldwide reputation to two dedicated archeologists, the German Karl Dörner

and the American Theresa Goel. (Ms. Goels ashes were strewn on top of the

mountain after her death.)

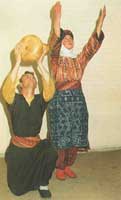

Kommagene started out as a kingdom that contained many ethnic groups. The early rulers knew that to rule effectively they had respect other cultures and especially other religions. This is the reason why so many reliefs of that period contain ceremonial handshakes. The official language of the kingdom was Greek, a language most likely alien to the local population. The language suggests that Kommagenes kings intended to bring civilization, Hellenic civilization that is, to this part of the world. Although they started out on a positive vein, eventually they alienated the locals, whom they viewed as inferior. When the Romans took over these lands, it is easy to imagine that the locals didnt put up a lot of resistance. Adiyaman has been the host of many civilization throughtout its history. Being a melting pot socially and culturally, it has valuable features related to customs about different periods of life, hospitality, folk dancing, carpets and kilims etc. Adiyaman is famous for its folk songs, folk dancers and tombs. Different kinds meatballs such as "cig kofte, icli kofte, mercimekli kofte" and hitap (stuffed hot pie) are special local foods in Adıyaman.The region of Adiyaman has throughout its history been witness to many different cultures. The first cultural development started with the Hittites when they decided to settle in this region. The Hittites laid the basis for the cultural development not only of Mesopotamia but also the cultures of the Mitannis, Urartus, Assyrians, Medes, Persians and Greeks all of whom left their traces behind. Later the Kommagene and Roman Empires enriched this cultural structure. Among the traditional dances the Halay dance has a very special significance. The most popular dances are: AgirHalay, DuzHalay, Berde, Derika, AGirhava, Dikhava, Lorke, Pekmezao, Tirpano and KurderoHalay. Songs like Uzun Hava are especially loved by the people because in them are expressed their sufferings and love.

Wedding Ceremony in Village Mustafa Erkmen |

Theatre Abuzer Caliskan |

A young lady Remzi Taskiran |

Serving Tea |

Adiyaman Region Dances and Costumes

Adıyaman is located between the upper Euphrates of

eastern and the middle Euphrates of southeastern Turkey. The province stretches

to the Euphrates valley in the east and the Aksu depression in the west. It is

bounded by the Malatya Mountains on the north and in the south it is made up of

valleys between countered hills.

Adıyaman

and the surrounding area was conquered in 1084 (13 years after the battle of

Malazgirt) by Buldaçı Bey , one of the commanders of Selcuk kingdoms

the founder, Kutalmışoğlu Süleyman Şah. The region

frequently changed hands between various powers in the region until finally it

was Turcofied by the Memluk Turks. Ottoman sultan Yavuz Sultan Selim made

Adıyaman a part of his domain in 1516. During the Ottaman rein, Adıyaman

was one of the 5 sancaks (like a county, with Samsat as the capital), of the

Dulkadir province. In the late 19th century, Adıyaman was made a

sancak in the Malatya province. In 1954 Malatya was carved up into two provinces

resulting in the creation of the Adıyaman province with the city of Adıyaman

as its provincial capital. Adıyaman has 8 provincial districts (counties):

Besni, Kahta, Samsat, Gölbaşı, Gerger, Çelikhan, Tut, and Tokaris.

Agriculture and animal husbandry are the main economic activities of the

province.

Adıyaman

and the surrounding area was conquered in 1084 (13 years after the battle of

Malazgirt) by Buldaçı Bey , one of the commanders of Selcuk kingdoms

the founder, Kutalmışoğlu Süleyman Şah. The region

frequently changed hands between various powers in the region until finally it

was Turcofied by the Memluk Turks. Ottoman sultan Yavuz Sultan Selim made

Adıyaman a part of his domain in 1516. During the Ottaman rein, Adıyaman

was one of the 5 sancaks (like a county, with Samsat as the capital), of the

Dulkadir province. In the late 19th century, Adıyaman was made a

sancak in the Malatya province. In 1954 Malatya was carved up into two provinces

resulting in the creation of the Adıyaman province with the city of Adıyaman

as its provincial capital. Adıyaman has 8 provincial districts (counties):

Besni, Kahta, Samsat, Gölbaşı, Gerger, Çelikhan, Tut, and Tokaris.

Agriculture and animal husbandry are the main economic activities of the

province.

Adıyaman

is one of the most significant places in Turkey archeologically as well as in

folk arts. Among archeological sites are the caves of Pirim in the capital city,

fortresses at Gerger and Samsat (now under the waters of the Atatürk Dam), and

the Cendere Bridge north of Kahta. But the most significant ruin in the province

is Mt. Nemrut, a ceremonial and burial tumulus for King Antiochus I of the

Kommagene kingdom. The site, about 7,500 feet above sea level has two terraces

(east and west) with gigantic statutes of the king and various Roman and Greek

gods.

Folk

dances of Adıyaman usually depict daily life or cultivation of the land.

Coeducational groups usually perform these dances, contrary to the Moslem

tradition of keeping sexes apart.

There

are however dances only for women or only for men. The live music for the dances

is usually provided by a drum and a Turkish oboe, called Zurna. The locals use

the term Gofend to describe a dance group. Sergofend is the term used for the

male at the head of the dance line, Başgofend for the female leader.

In

dances that that are more forceful and rigorous the performers are shoulder-

to-shoulder tightly clasping hands with dancers on the either side. For lighter

numbers the dancers join each other by hooking little gingers together. Shoulder

holding or shaking arms are not a part of Adıyaman folk dances. The

Chanting in Adıyaman dances is different than the ones in Gaziantep, Kars,

or Erzurum. Dancers belt out Tısss

Tısss

Tısss or

Ha

Ha

Ha

during their performance.

Local

Dancing & Everyday Costumes:

Men:

Men wear, under their caps, a hand-decorated colorful cloth called a Terlik

(sweat cloth) in order to absorb moisture during the dances. In some regions the

term Arakçin (in Arabic in meas sweat gatherer) is used for terlik. The dancers

wear a long-sleeved collarless, white or cream colored striped shirt with slits

along the sides. Over the shirt they wear a black or brown vest, kırkdüğme

(forty buttons), with woven fabric on the sides, silk material in the back. As

the name implies, the vest has forty buttons. For pants the men wear a black or

brown plain baggy trousers, called şalvar that is usually sewn from rough

goat hair fabric. These şalvars usually have no pockets and have wool

drawstrings strung through a silk housing by the belt area. A wool sash, usually

red, is tightly wrapped around the waist. The outfit is topped with a rough

hand-sewn half-sleeved brown coat, called aba. The front of aba is hand

decorated with various motifs. Hand-made wool socks with colorful decorations

are worn under leather moccasins. Men usually carry a white handkerchief.

black or brown vest, kırkdüğme

(forty buttons), with woven fabric on the sides, silk material in the back. As

the name implies, the vest has forty buttons. For pants the men wear a black or

brown plain baggy trousers, called şalvar that is usually sewn from rough

goat hair fabric. These şalvars usually have no pockets and have wool

drawstrings strung through a silk housing by the belt area. A wool sash, usually

red, is tightly wrapped around the waist. The outfit is topped with a rough

hand-sewn half-sleeved brown coat, called aba. The front of aba is hand

decorated with various motifs. Hand-made wool socks with colorful decorations

are worn under leather moccasins. Men usually carry a white handkerchief.

Women:

Women wear a crown that it bordered by a chain around the lower circumference.

Decorative coins (in the olden days gold) dangle from this chain. A gilded sash

is wrapped around the crown; a white cotton scarf (called Keten), is tied

crosswise in the front, is worn over the crown, leaving its front open. (An

unmarried woman does not wear the scarf.) Women braid their hair in two to six

strands; a decorative ditty with tassels, called Kezi, is worn across the

braided hair in the back.

Women

wear a loose, long-sleeved, knee-length cotton undershirt that is decorated in

various patterns. Mountain villages call this a Çit. Over the undershirt they

wear a long ankle-length, long-sleeved colorful dress. The striped dress, open

in the front, has slits in the sleeves as well as along the sides. The side

slits extends waist-high from the bottom dividing the lower half af the dress

into three pieces. This is the reason the dress is called üç etek (three

skirts.) Under the dress a pantaloon (red or rose colored), of silk or another

shinny material is worn. An apron, designed with wax-press tops off the outfit.

Hand-made wool socks of bright colors and moccasins complete the outfit.

Women

also wear decorative jewelry consisting of a silver or gold belt, a gold

necklace as well as matched bracelets and earrings.

In

the villages women wear a dress called Çotu or fistan. Decorative patches

usually adorn the dress around the waist. Under the dress they wear a long

cotton undershirt called kıras that is secured with a belt of the same

material. In all modes of dress, a long pantaloon, usually of shinny material is

worn as underpants. More recently, rubber shoes are worn instead of moccasins.

Women in the villages do not cover their faces.

Although

modern dress is the usual mode of dress in the cities, there are still women who

wear traditional outfits in the cities. But when they go out they cover

themselves, and their dress with a black wrap called çarşaf (shador in

Persian). Women covering themselves is a religious tradition.

Dances

of the Region: There are many dances of the Adıyaman region. Although it is not

possible to list them all, following is a partial list of them.

| 1. Simsimi | 2. Düz (Çeçen Kızı) | 3. Sevda | 4. Ağırlama |

| 5. Teşi | 6. Göçeri | 7. Çap (Takayak) | 8. Halay |

| 9.Rişko | 10. Galuç | 11. Kımıl | 12. Darık |

| 13. Hellican (With song) | 14. Göftan | 15. Tırgi | 16. Serjiri, |

| 17. İkiayak | 18. İriş | 19. Köfanjan | 20. Dıngi (With song) |

| 21. Fatmalı | 22. Sal(Boat) | 23. Keriboz | 24. Barış |

| 25. Kardeş Yolu (With song) |

Description

of Some Dances:

Sal (Boat): This dance depicts an ancient tragic event when a

boat, carrying a wedding party

(from a village in Samsat to Urfa), including the bride, capsizes in the

Euphrates resulting in the drowning of all in the boat.

At the start of the dance, men representing the

wedding party appear in a back-and-forth waving action representing the boat and

the people in it. Later the dance depicts the boat being caught in the current

and the attempt of the men to save it. Women appear, on heir knees, beating

their knees and chests while wailing (locals call it zılgıt) a

high-pitched lamentation. In the main dance line however, there is only one

woman, representing the bride. The dance concludes (after the symbolic sinking

of the boat) with the dancers singing a folk song, Euphrates, holding oars in

their hands.

Emines

mother hears of the

shooting and races to the marsh where the couple has fallen. She reaches them just as Bekiro and Emine are dieing. The song

he sings before his death

accompanies the dance.

Tırgi: Nomadic people spend their summers in high

grasslands, Çayi, and winters in lower elevations, Bozik. The legend takes

place in one of the permanent settlements of these nomads (called Yörük in

Turkish), Mıdın. A young woman, Aybekiris daughter Tırgi falls

in love with Seybe. Although it is not time yet to migrate to grasslands, her

family escapes to their summer home to escape rumors.

While there a rich family asks for Tırgis

hand for their son, and her father ascends. As tradition dictates it, Tıgri

accepts her fate without complaint. While she is taken to her betrothed however,

she asks to dismount her horse to pray. While praying she beseeches God to turn

her into a stone. Her wish is granted and she is turned into a mountain. This

mountain is called Tırgis Mountain to this day. The mountain is

considered sacred nowadays with young women tying wishing ribbons and other

ornaments to the trees on the mountain.

Sevda: This dance depicts the bounty of nomadic life. After

the milking of livestock, young women return to their tents in a merry mood.

They start to dance chanting tilili. Other young people of the camp join

the dance, making the dance a merry occasion of celebration.

Teşi: Teşi is an instrument used to spin wool. The

dance, performed in a line like hora, symbolizes the washing and spinning of the

wool.

Göçeri: This is another dance performed by nomadic people who

celebrate their arrival to a new place with a lovely dance that is performed by

a line of men and one of women facing each other.

Çep: This dance, performed in the mountainous regions,

symbolizes the grace and movements of a deer. The dancers keep rhythm to the

beat of a drum.

Halay: This dance is performed by the families of a couple

about to be married. The families show their joy of the impending event by

dancing together.

Rişko: This dance is performed during the harvest season to

celebrate the bounty of the land. Man and women dance in a line across from each

other. The characteristic of the dance is the graceful movement of the arms and

shoulders, especially at the start of it.

Galuç: This dance is from the Hallun village of Kahta and

depicts the struggle of the villagers fighting a poisonous weed called Geliç.

Village men get up early in the mornings before planting season to eradicate the

weed from the fields. At noon their women bring their lunch in buckets and water

in gourds. After lunch is consumed, men get back to work.

When finally the field is cleared of the weed, men

celebrate the occasion by performing the dance. Women joined them too. Women

carry the gourds on their shoulders during the dance and men go through symbolic

motion of chopping the weed with their sickles.

This is a fine dance that has won many awards in

international folk dance competitions.

Goftan: This dance tells the story of a young woman who falls

in love, during a wedding, with a man wearing a kaftan. She doesnt know his

name or identity but creates a dance in memory of the event.

Hallaç: Hallaç is a person who separated (before the

invention of cotton gin) cotton from seed by beating it. In the old days a hallaç

traveled from village to village, separating cotton from seed. One hallaç falls

in love with a young woman in a village of Kahta. He asks for her hand, but her

father refuses resulting in the elopement of the young couple. Her father upon

hearing this, has both of them shot

The dance, performed to the rhythm of cotton being

stroked, is accompanied by a sad song telling the tragic story of the young

couple.

Barış: This lively dance celebrates the peace that is struck between two feuding clans. The two families, to strengthen the bond between them, also inter-marry creating even more opportunities for celebration. The dance is performed by both men and women, and nowadays it celebrates love and friendship.

Go back to about Adiyaman / Geography / Social / Economy / Health / Education / Tourism / Sport / Transportation / Municipalities / Where does the name come from? / Adiyaman Museum / Local Newspapers / Wildflowers / Wildlife / Adiyaman Forum

![]()

Home | Ana

Sayfa | All About Turkey | Turkiye

hakkindaki Hersey | Turkish Road Map

| Historical Places in Adiyaman | Historical

Places in Turkey | Mt.Nemrut | Slide

Shows | Related Links | Guest

Book | Send a Postcard | | Disclaimer

|

|